The Signal and The Noise by Nate Silver is a must-read book for those interested in predictions. It is not a technical book. You will not learn any algorithm. However, it presents a series of real-world scenarios when predictions did work and where predictions did not work. The book is well written and is full of valuable references to support its arguments.

1. Anyone can beat an index fund

After all, any investor can do as well as the average investor with almost no effort. All he needs to do is buy an index fund that tracks the average of the S&P500. In so doing he will come extremely close to replicating the average portfolio of every other trader, from Harvard MBAs to noise traders to George Soros' hedge fund manager. You have to be really good -or foolhardy- to turn that proposition down.

2. Bayesian statistics is less wrong

Recently, however, some well-respected statisticians have begun to argue that frequentist statistics should no longer be taught to undergraduates.

Frequentist statistics emphasizes the purity of the experiment: every hypothesis could be tested to a perfect conclusion if only enough data were collected. These methods don't encourage us to think about the plausibility of our hypothesis.

3. A bug made Deep Blue beat Kasparov

But what had inspired Kasparov to commit this mistake? His anxiety over Deep Blue's forty-fourth move in the first game - the move in which the computer had moved its rook for no apparent purpose. Kasparov had concluded that the counterintuitive play must be a sign of superior intelligence. He had never considered that it was simply a bug.

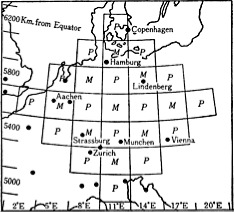

4. When predictions work - Weather

Weather predictions do not rely on statistics, nor on machine learning. They employ heavy simulations. The earth is split in cells, and the meteorological dynamics are simulated via well known models. The first weather simulation ever done is by the English physicist Lewis Fry Richardson in 1916.

5. When predictions don't work - Earthquakes

These processes may not literally be random, but they are so irreducibly complex (right down the last grain of sand) that it just won't be possible to predict them beyond a certain level.

6. When predictions don't work - Economics

Raw data for economics isn't much good.

"Why do people [economists ed.] not give intervals? Because they're embarrassed"

They are embarrassed because they are just too large.